This month’s Now We're Talking blog will explore a small slice of the folklore Michael J. Murphy wrote down based on his own life.

Wakes in Dromintee Parish, South Armagh Blog by Sean Hayes

In last month’s blog, we looked at the Irish Folklore Commission and Michael J. Murphy’s contribution to the National Folklore Collection. This month we would like to continue this theme by exploring a small slice of the folklore Michael J. Murphy wrote down based on his own life. The richness and depth of Murphy’s writing which can be seen throughout this collection really shines through here and shows how much there is to find within the collection.

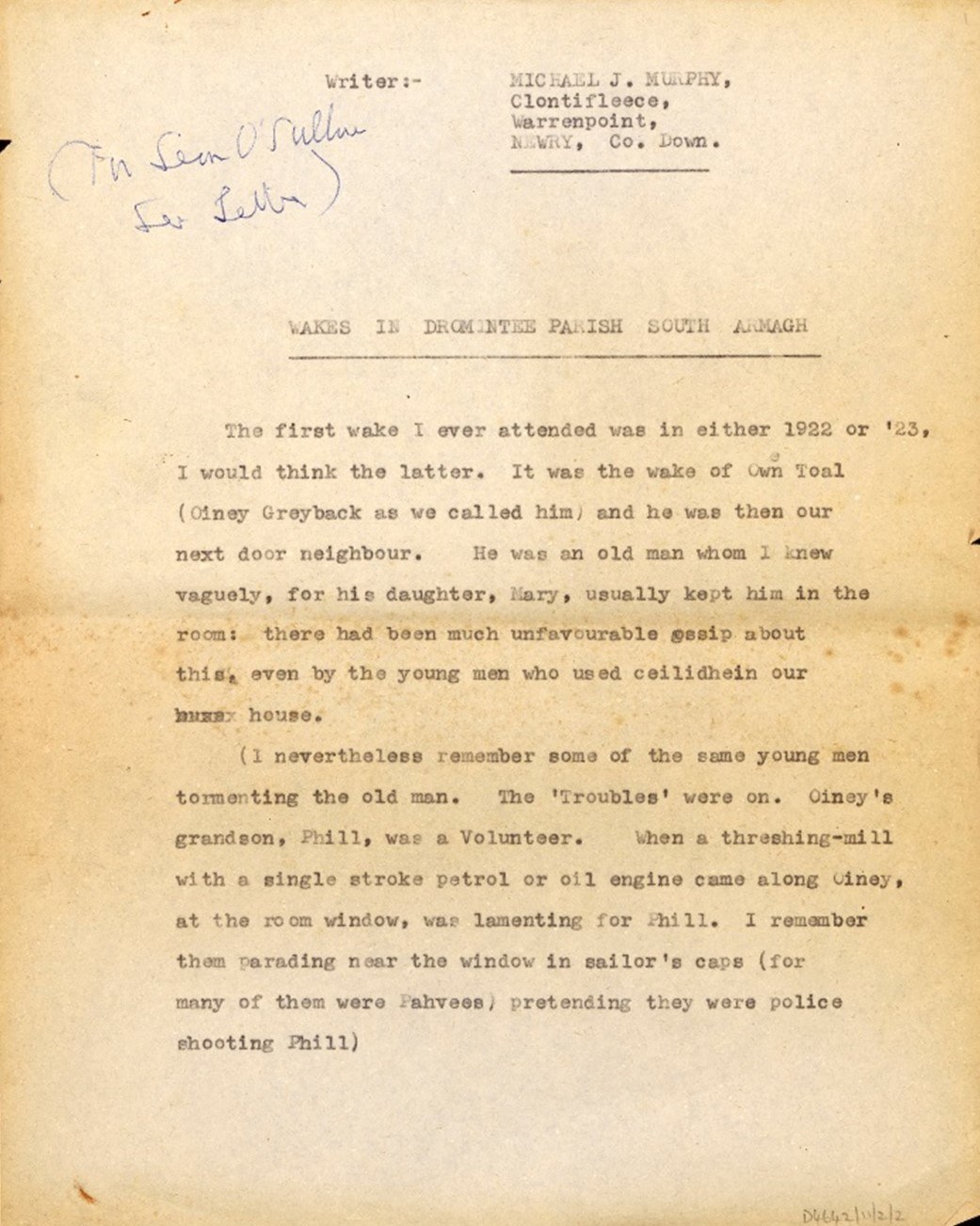

For this blog we are looking at a single research file that is packed with reflections from Murphy’s own childhood in Dromintee Parish in South Armagh (PRONI reference D4642/11/2/2). The 33-page file is bursting with life and humour from a distinctive cast of characters. The writing in this research file makes it clear why Michael J. Murphy was hired by the Folklore Commission and how he was such a successful collector of folklore.

In the file, Michael J. remembers the wakes he attended as a child. Throughout the 33-pages of reminiscence, Murphy paints a vivid picture of some of the more colourful aspects of rural life in South Armagh. He describes great parties which were well attended with games being played and, naturally, drink being consumed leading to some humour and mischief.

Murphy describes in detail the various wake games in his first book “At Slieve Gullion’s Foot”. The main game played at these wakes, as mentioned in some of these extracts, was “Marrying Out”. This involved a leader known as “The True Priest” who chose a girl from the crowd to sit in a chair. Three men would also join the game holding belts. The girl in the chair would then select a fourth man to join. The four men would walk around the girl holding their belts. Then “The True Priest” would call on one of them to give a song. If the song took too long to come, he would be hit with the belt by the man behind him. If the man was not a singer he “left his stick” on someone in the crowd asking them to sing for him. When a song had been sung the walking would continue and the next man asked to sing. The role of “The True Priest” was crucial to the game as he made witty commentary on all songs in the effort to embarrass the girl and the men much to the amusement of the crowd. He would eventually choose a man to “win” the girl in the chair and a new girl would be chosen and the game continued. The game really depended on the wit of “The True Priest”. A good “True Priest” could be called to wakes in outlying places to guarantee an enjoyable wake.

Some select passages have been chosen here that describe the antics of the wakes he experienced during his childhood in Dromintee. Each passage is a direct transcription of Murphy’s writing. They provide a clear window into the world Michael J. Murphy inhabited when he was growing up.

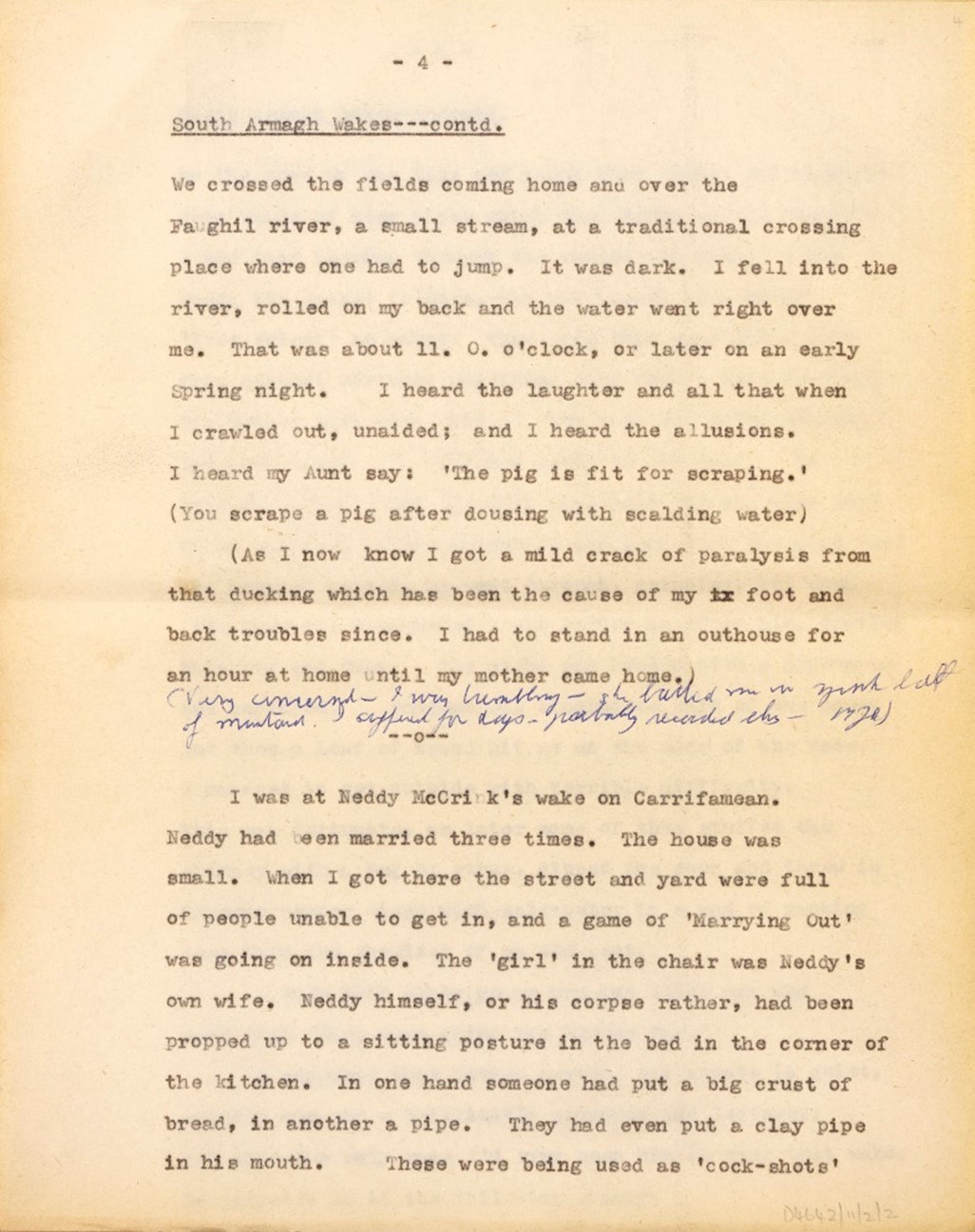

Neddy McCrink

I was at Neddy McCrink’s wake on Carrifamean. Neddy had been married three times. The house was small. When I got there the street and yard were full of people unable to get in, and a game of ‘Marrying Out’ was going on inside. The ‘girl’ in the chair was Neddy’s own wife. Neddy himself, or his corpse rather, had been propped up to a sitting posture in the bed in the corner of the kitchen. In one hand someone had put a big crust of bread, in another a pipe. They had even put a clay pipe in his mouth. These were being used as ‘cock-shots’ by the most of the boys and young men; their own missiles were heads of clay pipes which they broke off as required. I had been peering through the window and door. I was Paddy the Racker (O’Hare, who was famous locally as ‘True Priest’ as wakes: they used even send him a card from distant parishes adjoining ours when a wake occurred; his mother used burn most of them when she could before he had seen them) I followed Paddy to the door. He kept shouting: ‘Let the girl in — Holy Christ, what sort of unmannerly pack of whores are you — Let the girl in?’ The crowded parted, he went through, grinning and when the ruse was discovered I was hurled in after him, jostled this way and that. The globe was broken with a pipe-head and replaced. Someone was singing as part of the game. And then a loaf of bread hit me on the side of the face. I managed to get outside with terrible difficulty. This was fortunate, as later some of them stuffed the chimney with a bag of straw, closed the door and threw in Cayenne pepper mixed with salt-peter in a wad of packing taken from the shoulder of an old coat.

I left with other young men and older men who said that “they were going too bluddy far.”

I remember that Father Meenan, our curate (a quiet, saintly man and a brilliantly preacher and lecturer) got into the only rage I’d ever seen him in over that wake. He preached on it the following Sunday.

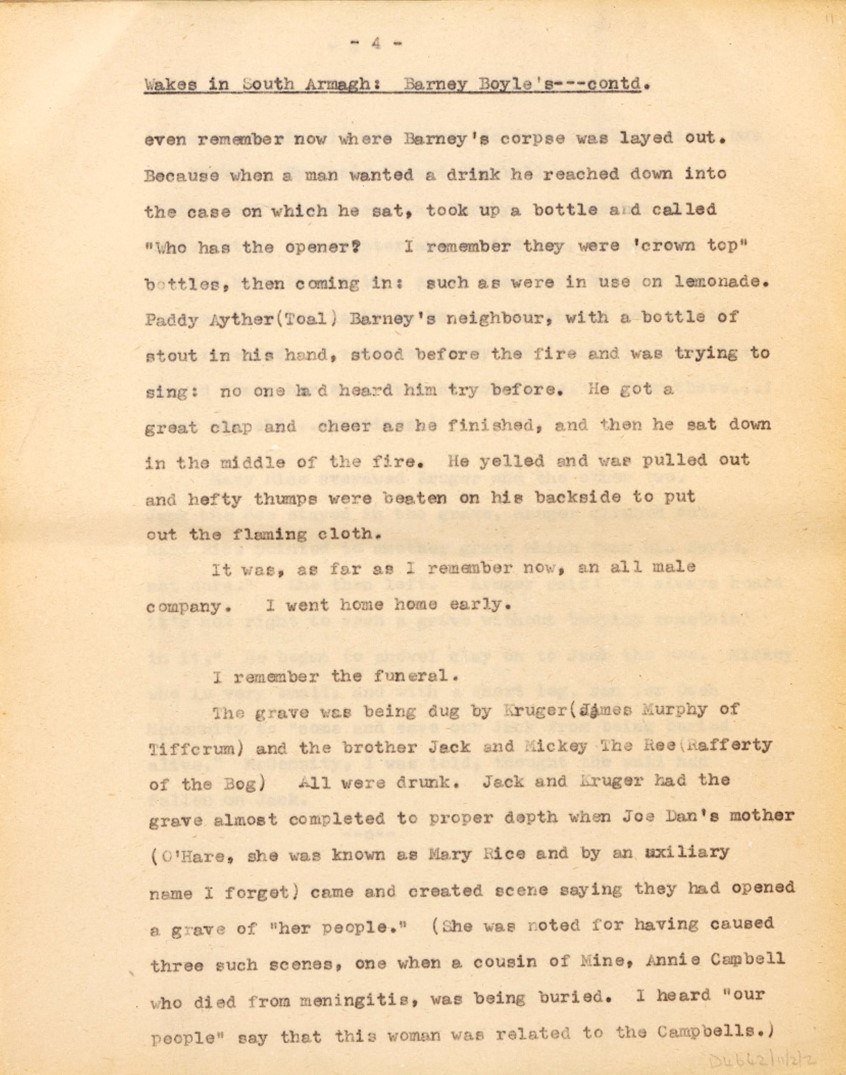

Barney Boyle

I was there that night at the wake. There were no chairs in the house: Barney used sit on a sack-covered stone. But everyone was seated, it seemed, on a case of stout. A “great bachin” of a fire of coal burned. There were pipes and tobacco galore. I don’t even remember now where Barney’s corpse was layed out. Because when a man wanted a drink he reached down into the case on which he sat, took up a bottle and called “Who has the opener?” I remember they were ‘crown’ top bottles, then coming in: such as were in use on lemonade. Paddy Ayther(Toal) Barney’s neighbour, with a bottle of stout in his hand, stood before the fire and was trying to sing: no one had heard him try before. He got a great clap and cheer as he finished, and then he sat down in the middle of the fire. He yelled and was pulled out and hefty thumps were beaten on his backside to put out the flaming cloth.

It was, as far as I remember now, an all male company. I went home home early.

I remember the funeral.

The grave was being dug by Kruger (James Murphy of Tiffcrum) and the brother Jack and Mickey The Ree (Rafferty of the Bog) All were drunk. Jack and Kruger had the grave almost completed to proper depth when Joe Dan’s mother (O’Hare, she was known as Mary Rice and by and auxiliary name I forget) came and created scene saying they had opened a grave of “her people.” (She was noted for having caused three such scenes, one when a cousin of Mine, Annie Campbell who died from meningitis, was buried. I heard “our people” say that this woman was related to the Campbells.) …

Mary Rice overawed Kruger and the other two. Jack the Ree stayed in the grave, Kruger climbed out. Mary Rice pointed to another grave which “was his Boyle, not ours.” She then left. Kruger said: “I always heard it’s not right to open a grave without burying somethin’ in it.” He began to shovel clay on to Jack the Ree. Mickey who is very small, and with a short leg, ran for Owen McGennity to “come and save our Jack from being buried alive.” McGennity, I was told, thought the wall had fallen on Jack.

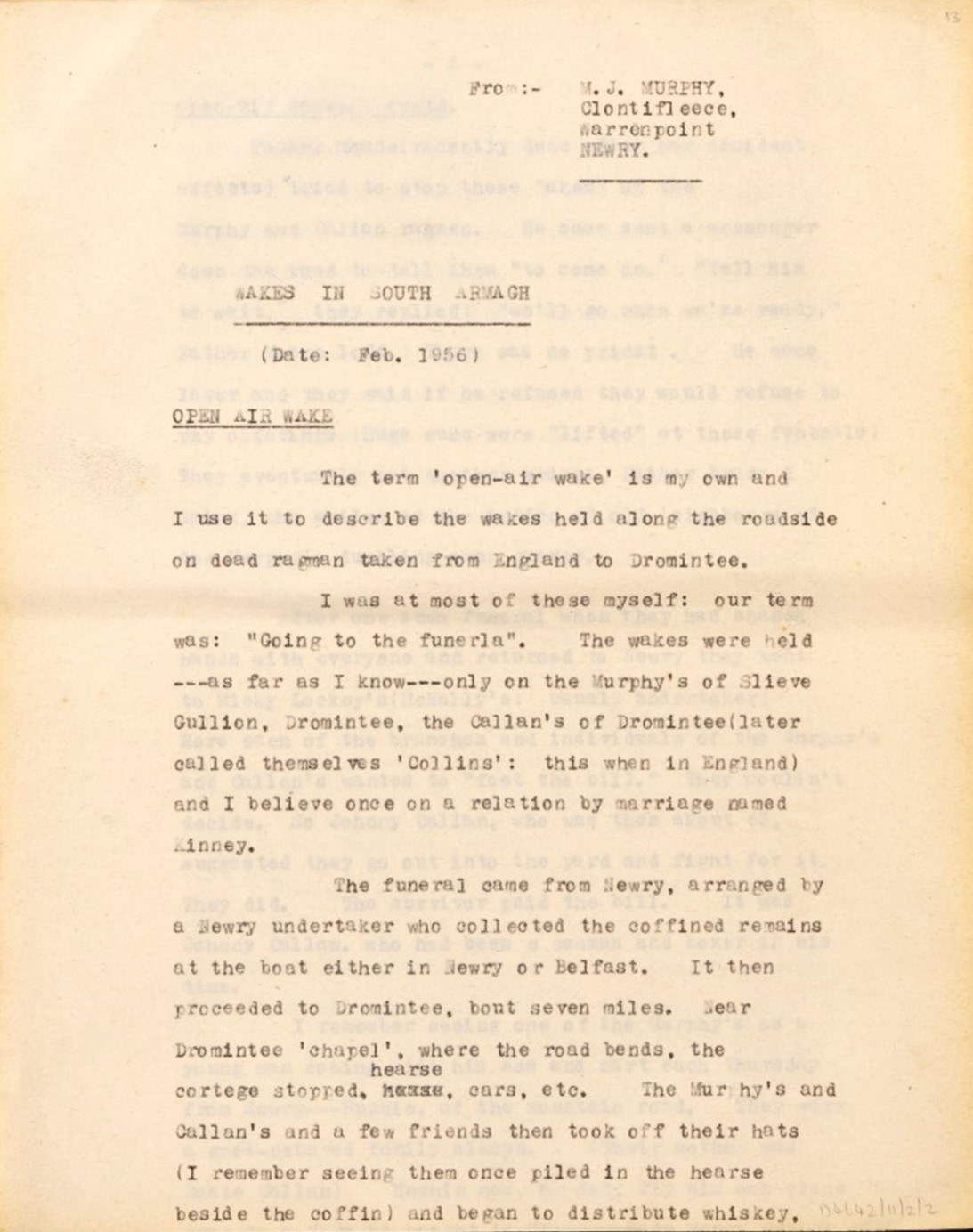

Open Air Wake

The term ‘open-air wake’ is my own and I use it to describe the wakes held along the roadside on dead ragman taken from England to Dromintee.

I was at most of these myself: Our term was: “Going to the funeral”. The wakes were held — as far as I know — only on the Murphy’s of Slieve Gullion, Dromintee, the Callan’s of Dromintee (later called themselves ‘Collins’: this when in England) and I believe once on a relation by marriage named Kinney.

The funeral came from Newry, arranged by a Newry undertaker who collected the coffined remains at the boat either in Newry or Belfast. It then proceeded to Dromintee, bout seven miles. Near Dromintee ‘chapel’, where the road bends, the cortege stopped, hearse, cars, etc. The Murphy’s and Callan’s and a few friends then took off their hats (I remember seeing them once piled in the hearse beside the coffin) and began to distribute whiskey.

Father Moane (recently dead after car accident effects) tried to stop these “(w)akes”[sic] of the Murphy and Callan ragmen. He once sent a messenger down the road to tell them “to come on.” “Tell him to wait,” they replied: “we’ll go when we’re ready.” Father Moane left. There was no priest. He came later and they said if he refused they would refuse to pay offerings (Huge sums were “lifted” at the funerals) They eventually got another priest, Father Brady I think, who smiled at the antics of old neighbours of the Murphy’s tumbling over graves.

After one such funeral when they had shaken hands with everyone and returned to Newry they went to Mickey Lockey’s (McNally’s: usually undertaker) Here each of the branches and individuals of the Murphy’s and Callan’s wanted to “foot the bill.” They couldn’t decide. So Johnny Callan, who was then about 63, suggested they go into the yard and fight for it. They did. The survivor paid the bill. It was Johnny Callan, who had been a seaman and boxer in his time.

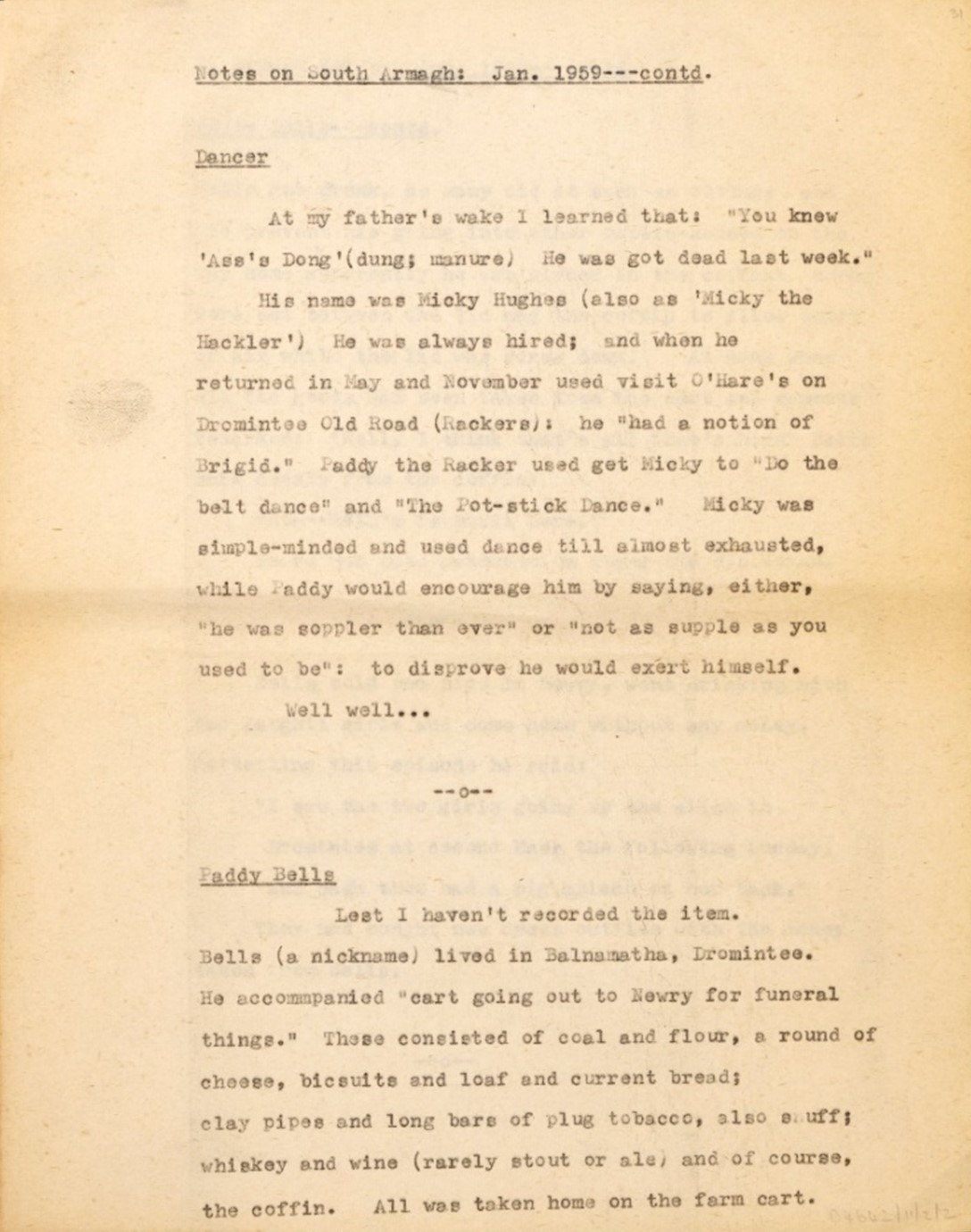

Paddy Bells

Lest I haven’t recorded the item. Bells (a nickname) lived in Balnamatha, Dromintee. He accompanied “cart going out to Newry for funeral things.” These consisted of coal and flour, a round of cheese, biscuits and loaf and current bread; clay pipes and long bars of plug tobacco, also snuff; whiskey and wine (rarely stout or ale) and course, the coffin. All was taken home on the farm cart.

Bells got drunk, as many did at such an outing; and to prevent his going into other public-houses on the way home apparently he was placed in the coffin to allow entry of air while the lid and the coffin to allow entry of air the goods had been taken from the cart and someone remarked: “Well, I think that’s all that’s here” Bells said deeply from the coffin:

“No — Bells is still here.”

There was pandemonium among the old women.

Conclusion

As you can see, a whole plethora of tales coming from one area of Michael J’s memories of growing up in Dromintee. This is only a small selection of a deeply interwoven collection that reaches far into every aspect of life. Many similar files are being made available to view online via the PRONI eCatalogue and on site in Tí Chulainn in Mullaghbane. Every file is as rich as the one highlighted here. It is certainly worth taking time to explore the interesting corners of this collection, you never know what you will find.

Find out more about the project via the Now We're Talking webpage.